City of Birmingham

Birmingham’s Neighborhood Association Network Faces Challenges at the 50-Year Mark

Donate today to help Birmingham stay informed.

“You don’t have to move to live in a better neighborhood” is a motto that circulated often during the early years of Birmingham’s 99 neighborhood associations, which began operating in the mid-1970s. The motto isn’t quoted much these days.

The neighborhood association network, often renowned as a model for cities across the country and world to follow, is marking its 50th anniversary amid concerns about its waning influence.

Resident participation has slid in recent decades, while officials with neighborhood associations say the city has deprioritized their work. They complain of long funding delays when they do have projects they want to complete and cite the city’s recent decision to send staff to meetings of the 23 community advisory committees, which encompass several associations, instead of focusing on the 99.

While opinions among residents, neighborhood leaders and city representatives differ regarding the challenges neighborhood associations face and possible solutions, there is consensus surrounding the value of the system as a vehicle for community empowerment and communication between residents and city leaders.

“It’s like a mechanism for the city to understand if a neighborhood actually wants something or doesn’t want it,” said Birmingham City Councilor Hunter Williams, a former president of the Crestline Neighborhood Association and one of several current city councilors whose political careers began with neighborhood association leadership.

Neighborhood associations, which meet once a month, vote on proposed zoning changes, business licenses and other matters, and those decisions are delivered to the City Council as recommendations. The city also allocates community-development dollars to neighborhood associations, which can use those funds for capital improvements, events, rehabilitation and beautification projects and to assist schools, libraries and other public institutions.

History of Success

Scotty Colson, a president of the Arlington West End and Crestwood North neighborhood associations during the 1980s and ’90s, also worked in the Birmingham mayor’s office for 35 years, often handling international affairs.

“We had people from Ukraine, we had people from the Soviet Union, when that still existed, from Japan and a couple other places come in to study our neighborhood program as a model for how to democratize and bring about citizen involvement,” Colson said.

In his own neighborhood of Crestwood North, Colson highlighted rezoning efforts and a housing redevelopment program as significant, neighborhood-led successes.

“In the mid-‘80s, Crestwood North was kind of on the bubble of where it was going to go,” he said. “And we did a major rezoning for the area to make it all single family. And that was one of the things that really started the revitalization of Crestwood North.”

The association also rehabilitated a couple of homes, sold them and used the proceeds to rehab more housing. “And pretty soon it had created a virtuous cycle of people coming in and redoing the homes,” Colson said.

Adrienne Reynolds, president of the Enon Ridge Neighborhood Association and the Smithfield community, said associations in her community are active in the area’s schools and have held neighborhood cleanups, established a pocket park and supported various community events and projects, including a holiday social event at Parker High School.

“This past year, we did it a little bit different,” she said of the holiday event. “We solicited funds to give to each of the schools (Tuggle Elementary, Wilkerson Middle and Parker High). We gave two families at each of the schools Visa cards totaling $200 each.”

City Councilor Valerie Abbott, who served as president of the Glen Iris Neighborhood Association for about 14 years, said rezoning that neighborhood to all single-family residences was an important goal the association achieved, along with tree plantings, restoration of a spring in a park, construction of softball fields and, most recently, the building of a playground accessible to kids with disabilities.

“We’ve been talking about it for at least 10 years, and it’s finally coming to fruition,” she said.

A recent success in the Echo Highlands neighborhood was working with the city to implement traffic-calming measures that have reduced speeding, said William Harden Jr., president of that neighborhood’s association.

Councilor Williams noted a recent case in which a neighborhood’s strong opposition to a proposed business led to the City Council’s decision to not grant the business a liquor license.

Birmingham’s neighborhood associations have been big players on the national scene through Neighborhoods USA, a nonprofit that launched in 1975 to connect neighborhood associations across the country. NUSA holds an annual conference with workshops and presents awards that recognize work being done in neighborhoods.

“NUSA as an organization has been like a hub for neighborhood associations to be able to expand and to be able to thrive and get resources, not only from the federal government but also from their city,” said Precious McKesson, NUSA board president. “Birmingham has been one of the largest delegations that participates in NUSA every year, and they’ve been award winners for numerous areas.”

In 2023, NUSA selected Birmingham’s Woodlawn neighborhood for one of its top honors, the Neighborhood of the Year award in the category of physical revitalization/beautification. The same year, NUSA awarded the Five Points neighborhood second place in the multi-neighborhood partnership category.

Outgrowth of the Civil Rights Movement

Development of neighborhood associations began in the early 1970s in Birmingham and other U.S. cities, largely to meet citizen-participation requirements for receiving federal funding through the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grants.

Birmingham was a national leader in devising a citizen-participation program. Like many structures and institutions in the city, citizen participation in governance and planning has its roots in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

“Perhaps due to the citizens’ active role in the changes born out of that chaotic decade, by the 1970s Birmingham became a pioneer in citizen-centered planning,” states a 2011 case study of the Birmingham Citizen Participation Program by A Committee for a Better New Orleans, written when that organization was reviewing other cities’ participation programs to develop a model for New Orleans.

In 1963, Birmingham had established the 212-member Community Affairs Committee, the city’s first formal interracial participation body, which had 23 Black members at its inception and was charged with advising the mayor and council on improving the city and its race relations.

During 1973 and much of 1974, the city’s Community Development Department and mayor’s office worked with HUD and residents to draft a Citizen Participation Plan, which was approved in October 1974, less than two months after President Gerald Ford signed the law that established the Community Development Block Grants program.

A campaign to inform residents of the program followed, and the three-tiered network — composed of neighborhood associations, community advisory committees and the Citizens Advisory Board — began operating in 1975.

While neighborhood borders were based on Birmingham’s historic segregation and red lining, the CPP gave Black communities a level of influence that had not been possible previously.

“With adoption of the Citizen Participation Plan in 1974, Birmingham had reversed the city’s longtime tradition of denying its Black citizens the opportunity to participate in the planning process,” Charles E. Connerly wrote in “The Most Segregated City in America: City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920-1980.”

Birmingham’s first Black mayor, Richard Arrington, who was elected in 1979 after serving on the City Council beginning in 1973, told the Birmingham Times in 2023 that the Citizen Participation Plan was second only to the national Voting Rights Act of 1965 in the level of political strength it gave Birmingham’s Black residents in the 1970s.

“Every community was organized, Black and white, and the Black communities especially, like North Birmingham and West End,” Arrington told the Birmingham Times. “All of the Black communities were better organized, as a result of that block grant program, than they’d ever been before.”

A 1977 HUD report showed only 10 cities — Birmingham among them — of the 558 receiving the grants had a participation program in which all citizen members were elected.

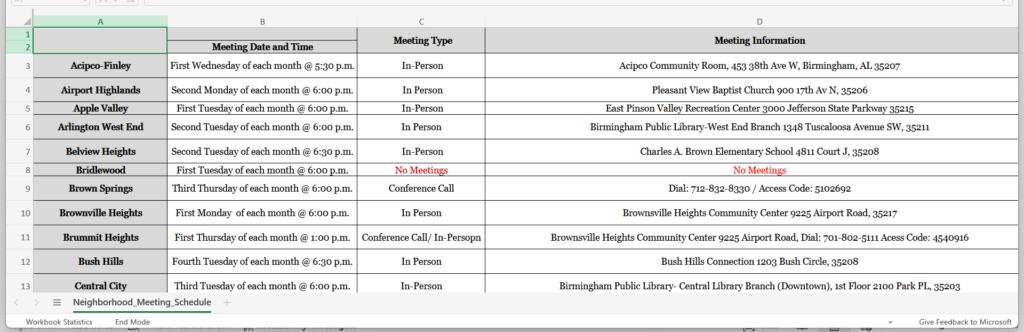

Through the Citizen Participation Plan, which was revised in 1980, 1995, 2006 and 2013, Birmingham currently is divided into 23 communities, and those communities are made up of 99 neighborhoods, each of which operates a neighborhood association.

Every neighborhood elects three officers — president, vice president and secretary — who serve as members of community advisory committees. The presidents of the 23 communities form the Birmingham Citizens Advisory Board, which holds a public meeting monthly and has regular meetings with the mayor and City Council and as-needed meetings with city-department leaders.

Birmingham’s Community Resource Services Division, organized under the mayor’s office, now serves as the liaison between neighborhood associations and local government.

“We assist in a number of ways with getting projects done if they have issues and concerns in the neighborhood,” said Alice Williams, deputy director of the Community Resource Services Division. “We try to be that voice that they don’t have at City Hall, because everyone doesn’t have a point of contact here.”

The Community Resource Services Division employs seven community resource representatives who are assigned to particular communities. While the Citizen Participation Plan does not require resource representatives to attend community or neighborhood meetings, most of which are held in the evening, they go to as many as they can, Alice Williams said.

“We try our best,” Alice Williams said. “This job is not just from six to seven in the evening. They (resource representatives) should have a relationship where they can talk to any of those officers, hear their complaints, concerns and issues during the day. So, we try to figure out ways that we can address the concerns that they have prior to those meetings.”

Waning Participation

Officials and residents connected with the neighborhood organization said poorly attended meetings are a threat to the effective operation of many neighborhood associations.

While many residents viewed neighborhood meetings as events not to be missed decades ago, 30 to 40 people is a crowd at a neighborhood association meeting in 2025, and gatherings of three to five residents are not uncommon.

In January, Councilor Williams wrote an opinion piece that called for blowing up and rebuilding the neighborhood association process. He suggested developing a secure, online voting platform to increase participation.

“When we’re asking for a neighborhood vote, we’re trying to get the pulse of the neighborhood, so the more people that participate in the vote, the better,” he said. “And when you have neighborhood meetings that require in-person voting, and that’s the only method of voting, I’m not sure that we’re actually getting a sense of what these neighborhoods want as a whole. We’re getting a sense of what the people that show up to the neighborhood meeting want.”

Thirty-four neighborhood associations hold virtual, conference-call or hybrid meetings, but most association meetings are in-person only, and all voting must be done in person. Information about the neighborhood meeting schedules and events can be found on this city website.

Less than 1% of residents vote on issues in most neighborhood associations, Hunter Williams said, pointing to in-person meetings as the main obstacle.

“Some of them are literally during the middle of a work day,” he said. “Some of them are later at night, when people with jobs that don’t coincide with the schedule can’t go, or they have a family. Back in 1975, a physical, in-person meeting to hold a vote was the only way to do it. But now that technology has changed, there’s so much of stuff that we do online, from renewing your driver’s license to paying your taxes to renewing your car tag. It kind of makes sense to have voting done where residents can read about it, understand what it is for themselves and cast a vote without having to go to an in-person system.”

Hunter Williams said setting up a remote, secure voting system for all 99 neighborhood associations would require buy-in from CAB, alteration of the Citizens Participation Plan, support from the council and funding to develop an online voting platform.

Buy-in from city staff, particularly those in the mayor’s office, also would be needed to ensure content residents would need to make informed decisions is uploaded to the system.

McKesson, of NUSA, questioned the wisdom of allowing virtual voting, however, especially when someone hasn’t attended the meeting, because they might not take the time to fully understand an issue before voting on it.

Other perspectives exist on why neighborhood meeting attendance has declined and what could reinvigorate it. Many of these views are related to funding and other support from the city.

Funding for the neighborhood association system now comes through the city budget rather than CDBGs. Federal funding had come with generous appropriations for neighborhood associations, Colson said.

“After federal funding ended, you had the creation of city funding, and a lot of neighborhoods had money at the bank anyway, so they were able to do stuff for several years after federal funding ended,” Colson said.

City funding for neighborhood projects was cut from $10,000 to $2,000 per year for each neighborhood during former Mayor Larry Langford’s administration, from late 2007 to late 2009, Abbott said.

Several leaders and residents said the loss of neighborhood newsletters or flyers the city used to pay to mail to all addresses in each neighborhood has affected turnout. These notices told residents when neighborhood association meetings would be held and what topics would be discussed.

“Some neighborhoods don’t have much participation, and I hand that to the administration of the city for cutting out the communications money,” Abbott said. “When the city stopped giving good support to the neighborhoods, they began to have problems. When you received a flyer in the mail that told you what was going on at the next meeting and the synopsis of what happened at the last meeting, and talking about neighborhood initiatives and work days and tree-planting projects and all these things that got people’s participation and their enthusiasm up. When all that went silent, people went back to watching television.”

Without the newsletters, Harden said, neighborhood leaders have limited methods, such as signs, banners and going door-to-door, to even inform residents that their neighborhood associations exist.

“There have been some conversations from the administration about incorporating more of that neighborhood information in some of the mailers that they send out to us in the mail,” said Harden, who is vice president of the Citizens Advisory Board. “That would be helpful in, obviously, improving awareness.”

While the city recommends neighborhood associations use a platform that allows them to send mass emails, texts and phone messages, doing so requires neighborhood associations to have residents’ phone numbers and email addresses, which they can only collect when residents sign in at meetings.

“We have a website, but somebody would have to know about the neighborhood,” Harden said. “So, I’m hoping there’s some future discussions that we can have with the city to potentially correct some of those pitfalls in the process.”

Alice Williams of the Community Resource Services Division said neighborhoods could use part of the $2,000 the city allots them each year to buy computers and printers for producing newsletters. She said her office also encourages neighborhood leaders to create Facebook pages and use other electronic means to share meeting notifications.

Birmingham City Schools has a text thread neighborhoods could use to let parents know about meetings, she continued, and the city pays for neighborhood signage with meeting dates and times.

“So we give them the resources,” she said. “It’s just if they opt to use them. Our rec centers and our libraries are also great resources. We encourage them to get a flyer up in those spaces. You can’t expect people to come to you if you’re not sharing that message.”

McKesson, of Neighborhoods USA, said Birmingham is not the only city dealing with low participation at neighborhood meetings.

“Across the nation, we’re seeing a decline in certain neighborhood associations, where people are not as active as they used to be,” she said. She also recommended reaching out to renters as well as using Facebook pages, holding virtual meetings and putting interesting speakers and topics that are impacting the community on the agenda.

“We also have to make sure that we’re not excluding our older residents who may not know how to use computers or may have limited access to the internet,” McKesson said. “So, you just want to make sure you’re not putting up a barrier that’s going to exclude someone.”

Funding Delays

Neighborhood association leaders have complained in recent years about the length of time it takes to receive funding from the city.

“It can be a long process to get a project from conception to reality,” said Harden, who became an active member of the Echo Highlands neighborhood association in 2014 and president in 2018. “So that is something that obviously we’d love to get improved. We hope to continue to have conversation with the administration as it relates to that.”

Reynolds, who was secretary of CAB for more than 10 years until the end of last year, said the city’s approval process can be problematic.

“For instance, if we wanted to use some of our funds for a capital project or something that the city allows us to use our funds for … something like getting a new sign in your neighborhood or even to fix a certain part of the sidewalk, it takes forever just to get that particular project through City Hall,” Reynolds said.

After a neighborhood association votes to approve a project, leaders must turn in to their community resource officer the minutes and sign-in sheet of the meeting in which the project was approved, then the paperwork advances to the city’s legal department, the council’s Budget and Finance Committee and finally to the full council, said Alice Williams.

She said projects move through the system quickly unless documents are missing or external agencies such as the Alabama Department of Transportation are involved.

Reynolds said certain recurring requests, such as those for neighborhood events, tickets to the Martin Luther King Jr. Unity Breakfast or for funds to send representatives to the Neighborhoods USA conference, are the only ones that move through the process quickly and easily. Other requests, she said, can span neighborhood administrations.

“You keep calling back, checking on it, has this been approved?” she said. “Sometimes the community resource person knows what’s going on with it, sometimes they don’t. They may call you back, they may not. And by the time it gets through all of the loops and hoops that (it) has to go through … most times you’re out of office, unless you choose to come back in office. And if you’re not back in office, unless you properly tell the other administration coming in what’s going on, it gets lost in the shuffle.”

Harden said that, depending on the type of project, the steps a funding request must go through can add significant time.

“By the time you actually receive the approval, inflation occurs, things happen, and the price may not be the same price as you originally started off with,” he said.

Alice Williams said that for the most part, the Community Resource Services Division gets projects turned around as soon as possible. “I find it hard to believe that we’ve got any outstanding projects like that,” she said.

There is an issue, she continued, with neighborhood associations not turning in necessary documents with their requests.

“If it’s incomplete, we can’t process it, because there are state guidelines that we have to adhere to that require certain documentation,” Alice Williams said.

Reynolds maintained that problems reside mostly at City Hall and possibly stem from poor transfers when staff changes.

“You have people in positions at City Hall who don’t know or understand all of the processes that are already in place,” she said. “There have been several times that I’ve had to show people on the other side where you go to find this, that and the other. I don’t mind doing that. I’ll help out where I can.”

But she’s also turned to other sources of funding for the Enon Ridge Neighborhood Association. The association operates a 501(c)(3) organization that receives funding through donations and sponsorships.

Hunter Williams said the bidding system, vendor selection and more regulations make the process of spending municipal funds more cumbersome than it would be in the private sector.

“Being a former neighborhood officer, I share that frustration,” he said. “Being on the City Council, I share that frustration still today that the government process is just slow.”

Less Power Over City Government

Colson said neighborhood associations once held a lot of power.

“A lot of the political organization was tied to neighborhood associations,” he said. “So, candidates would come and talk with the neighborhood associations. It was very important. And when you have that, and when you know that the council is going to give some credence to what the neighborhood says, it empowers. It’s like, ‘OK, we can do something.’”

Hunter Williams said some neighborhood associations — the ones with the most people showing up — still have that kind of influence.

“In number, there’s power,” he said. “The more people that participate, the more influential the organization.”

Reynolds, a former CAB officer, said she believes the city respects the positions of CAB officers and listens to their requests and answers their questions, but the effectiveness of the process is questionable and depends on the city administration. With this administration, she said she doesn’t see much response when CAB brings up something.

“If you were asking me how would we resolve it, the answer would be to come to the table and talk about it and see how we can get these things moving, which is part of what the CAB is supposed to do,” Reynolds said. “They do come. We do talk, but that’s usually where it ends.”

Abbott said neighborhood associations used to have regular contact with city officials and receive more assistance from community resource officers.

“I don’t think the citizens are the problem,” she said. “I think the lack of support for the program by the city that created it is. There are even a few people on the City Council who they’d like to see it go, but I think it’s because they have difficulties with people at the neighborhood meetings who want them to do things that they’re maybe not doing.”

Changes Ahead

Recent communication from the Community Resource Services Division to neighborhood leaders about city staff prioritizing the 23 community meetings rather than neighborhood meetings has drawn concern from some residents.

Alice Williams said attending all 99 monthly neighborhood meetings, some of which are on the same nights, is impossible for city staff, and she has attended meetings where staff outnumbered residents.

“What I was saying to our neighborhoods was, let me try to come up with a way that I can guarantee that if you say, ‘Alice, we’re having trouble with the Department of Transportation not paving over here,’ next month, at your community meeting, I will ask them to prepare everything they can for your community.

“That was me saying, ‘This is what I’m going to try to do, because, based on what I see, they’re not coming to your meetings. I have no control over that.’ So, I was trying to get what I could for my neighborhoods.”

Hunter Williams said that, while city staff are not present at every meeting, they spend significant time ensuring information is provided to neighborhood associations.

Ideas for improving the neighborhood association network have included redrawing neighborhood boundaries and reducing the number of neighborhoods to reflect Birmingham’s smaller population compared to 1975.

Consolidating some associations could create a stronger critical mass of residents, Colson said.

“A lot of the neighborhood boundaries really are not rational at this point, because they’re the same boundaries they were 50 years ago, and that, I think, might be a way to address the number of neighborhood associations,” he said.

The Citizens Participation Plan requires that neighborhood boundaries and names be reviewed every two years, but altering borders requires the agreement of all affected neighborhood associations. Changes to the neighborhood map have been rare, except to accommodate newly annexed areas.

Hunter Williams said that, in the district he represents, the integrity of the neighborhood lines is still valid.

“Maybe that makes sense in a one-off scenario, but I don’t see that as being necessary in the area that I represent,” he said.

Abbott advocated for restoring newsletter funding and increasing the number of community resource representatives.

“If the city’s support and enthusiasm was behind this program, it would still be working well,” she said.

She also encouraged collaborative projects between the city and neighborhood associations, where both contribute financially. “The best way to get the city to move on something is to pitch in some money,” she advised.

Focusing on tangible projects that benefit communities long-term is more effective than prioritizing social events, she said.

“A lot of neighborhoods have a big fun day. But it doesn’t fix a darn thing in your neighborhood,” she said.

Mentioning difficulty in attracting leaders and volunteers, Colson said generating citizen participation could revitalize neighborhood associations.

“The key is not to say, ‘OK, we’re just not going to do it anymore,’” he said. “The key is, ‘How can we do this differently?”

Reynolds also said it’s important for neighborhood associations to continue.

“Everything starts with a root, and the neighborhood is the root that blossoms into a community,” she said. “You can’t have flowers on the top without a root at the bottom. You just can’t have it without the neighborhood, and that needs to be rethought and reworked so that you can keep your root and grow from there. Sure, you can branch out to various things, but you got to keep your root.”