Education

Jefferson County School Leader Becomes the National Face of Education

Donate today to help Birmingham stay informed.

Walter Gonsoulin is used to being the face of Jefferson County Schools. The superintendent makes frequent visits to schools from McCalla to Mount Olive and Center Point to Concord.

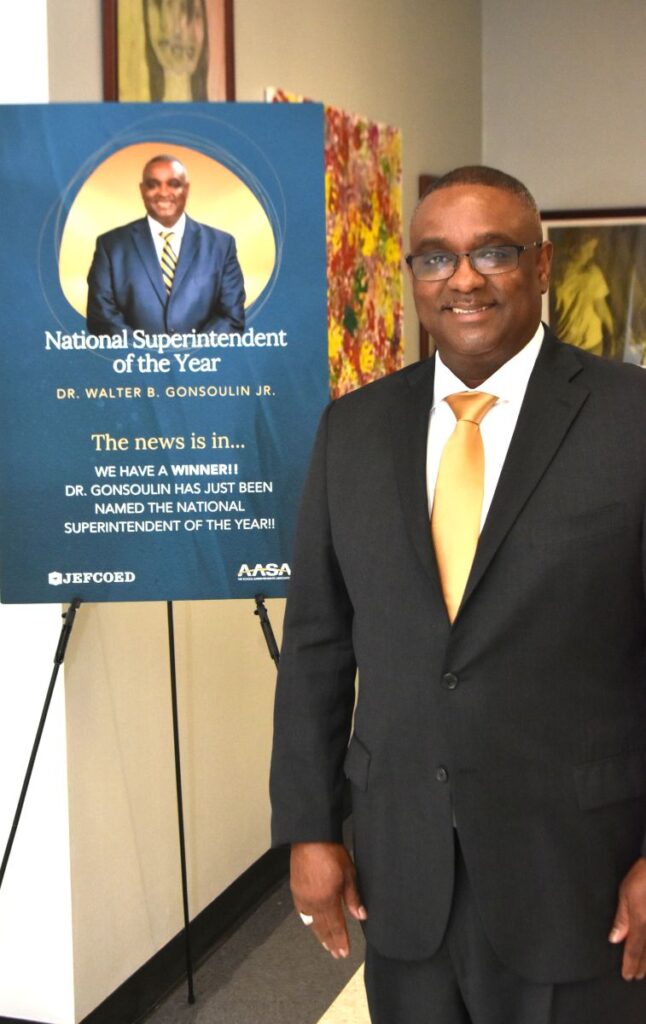

These days, Gonsoulin is getting more face time, even when he’s not physically in the room. Several posters and banners with Gonsoulin’s face can now be found at the school system office, including one that hangs over the front entrance.

Last week, he emerged from 49 entrants to be named National Superintendent of the Year by AASA, The School Superintendents Association, making him the face of education across the country.

Gonsoulin is the 38th superintendent to receive this honor and the first from Alabama.

“I do feel the spotlight,” said Gonsoulin, who is eight years into his tenure with Jefferson County Schools, six of those as the system’s top educator. “Day by day, it’s becoming more and more of a reality, especially recently. I got sent a YouTube video and it’s Congresswoman Terry Sewell giving a proclamation on the floor of the chamber.”

A picture of Gonsoulin was on an easel as the District 7 congresswoman lauded Jefferson County’s system leader.

“To see that, man, I’m like, not too many people get a chance to experience that,” he said. “This is something different.”

Just days before Gonsoulin was recognized as the top superintendent, he celebrated another victory. The county reached an agreement in a 60-year-old lawsuit alleging racial inequalities in education at its schools. A federal judge earlier this month signed a consent order approving the county’s proposal to eliminate those inequalities.

Gonsoulin said he believes in never compromising on education for all the children the school system is tasked to serve.

“I wanted to stand firm on the fact that, whatever we do, it’s gonna be for all children,” he said. “Not just Black children, not just brown children but white children, yellow children. And if I leave one out, we can add that one too.”

Before becoming superintendent of the Jefferson County system, Gonsoulin was the superintendent of Fairfield City Schools. During that term, he initially took offense when he heard a speaker at an event say that some students were limited by their ZIP codes, citing Fairfield as an example. Then a road trip to visit school systems within a 30-minute drive of the one he led helped him realize the assertion was true.

The superintendent committed himself to changing that situation, and he continues to do that now with Jefferson County.

“I created a mindset about education then, that we should never lessen the quality of education based upon a child’s ZIP code.”

Toward that end, Gonsoulin led Jefferson County in the creation of Signature Academies, which allows students to go to nearby high schools that are outside of their attendance zone and take courses not offered at their school.

For instance, Center Point, Mortimer Jordan and Pinson Valley high schools are in the northern “cluster” zone. “We put quality programs at each one of those schools,” he said. “We allow children, (if) they were going to Mortimer Jordan as a base school, we allowed them to attend those other schools and be a part of those academies if they were interested in them, and vice versa.”

The school system allotted $1 million to provide transportation to students from their base school to their new school. Wi-Fi is provided on those buses so travel delays don’t rob students of a moment of study time.

“Children at Center Point, if they were interested in culinary, if they were interested in creative design and they want to be a part of that, all they have to do is apply,” the superintendent said. “It took them outside of their ZIP code, and we exposed them to quality programs.”

Students have been going to their cluster schools part time, but beginning in the fall, students who choose to be in certain programs will be able to go to that school full time.

In dealing with racially inequality in schools, Gonsoulin recalled a time when some wanted to force changes in district attendance zones. He was firmly against that.

“With respect, I thought that was an antiquated model,” Gonsoulin said. “You don’t force people to do something because they’re not really committed. And, believe it or not, people choose to live where they live. There’s a reason why they live there.”

That’s not an issue with the academies.

“I didn’t have to force a white child to go to a school that was predominantly Black,” he said. “I didn’t have to force a Black child to go to a school that was predominantly white.”

The superintendent cited a student who is zoned to predominantly white Oak Grove High but aspires to reach West Point and wants to be part of the Junior ROTC program at Pleasant Grove High, which is predominantly Black.

The superintendent said Signature Academies help make commencement a true beginning.

To that end, the school system has partnered with the Jefferson County Personnel Board and business leaders to offer educational opportunities that align with the job market. “We partnered with businesses within a 50-mile radius because we realize that 70% of our children stay in that area.”

“We look at the high-interest, high-wage jobs and we create those programs in our schools,” Gonsoulin said. “Therefore, those children have the credentials. And we don’t stop there.”

System leaders meet with various industries once a quarter. For instance, they asked leaders in the health care industry where they had vacancies. The answer was patient care technicians.

Gonsoulin and other system leaders asked how many vacancies are in that field and were told 60. A check of the 2,600 graduating Jefferson County students showed that 85 of those students had the proper certification for the position at that time.

“I told him. this is your workforce,” the superintendent said. “Your job, and our job, is to get these children in interviews.”

About 47 of those students had signed contracts for jobs before they graduated. “And we do that in each one of the categories that we have,” the superintendent said. “In construction, we had 35 children last year that got jobs and signed those contracts. And these children (will make) $50,000, $60,000, $70,000.”

Gonsoulin’s commitment to eliminating racial inequalities and preparing students for life in college or the workforce were among the reasons he was singled out in the search for the National Superintendent of the Year.

When he was chosen as a finalist for the award, the stage was set for him to be announced the winner in his home state of Louisiana. He grew up in New Iberia, the oldest and only son of six children.

“I grew up in a community and in a family with the mindset that we could do whatever we wanted to do,” the superintendent said. “There were no limits. (His parents and other adults) believed in you and they took care of you to help hone and harness that energy.”